We Left Our Afghan Allies for Dead. A Former Interpreter and Marine Are Bringing Them Back

Haseeb always kept an extra bullet for himself.

Alone, and in the middle of the desert, he remembered the bullet. When a car pulled in front of his taxi, he quickly stashed his computer under the floorboard and gripped the paperwork he was tasked to deliver to Kabul. Six men then stepped out of the other vehicle, and his heart sank.

The Taliban had stopped him.

Haseeb knew what awaited Afghan interpreters helping American Forces—torture and death—but remained calm as he exited the vehicle. He knew the Taliban, used to interrogating Afghans, would view inconsistencies in his story as a source of suspicion and doubt. Haseeb remained neutral, explained why he was leaving Bamiyan for Kabul for a work project, and braced himself for whatever might come next.

Several tense moments passed, but Haseeb’s story checked out, and the men let him leave. Once out of sight of the Taliban, Haseeb broke down in tears.

This wasn’t the first time Haseeb’s life had been threatened. On his way to the capital one afternoon, a rocket-propelled grenade hit his convoy. He was certain that this would be the time he finally got captured.

In another incident, Haseeb was at the police headquarters in Kandahar with a group of advisors from the 101st Airborne and three other interpreters when something exploded. That explosion was followed by a second, then a third right next to the wall where he’d been standing. He survived unscathed and helped communicate the events to U.S. troops.

Desite the dangers, Haseeb was well aware of what was at stake, and continued to risk his life.

…

Haseeb was a boy when his father, a famous Afghan hatmaker, fled with his family to Pakistan rather than live in Afghanistan under Sharia Law. When Americans removed the Taliban from power, they returned.

“Under the Taliban, my neighbors were starving. Once the Americans took over, we got to experience democracy… [My neighbors] had cars, houses, and never worried about food,” Haseeb recalled.

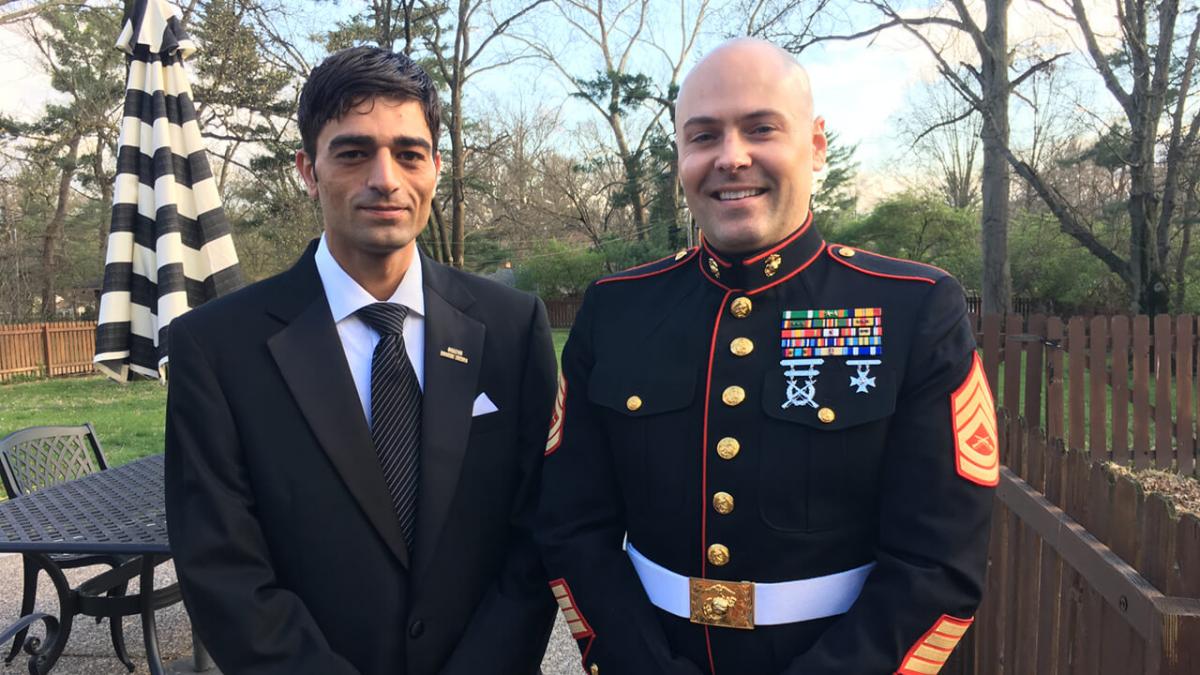

Haseeb hadn’t always spoken English, but as a young teen, he found himself fascinated by the language. One of his brothers advised him the language would help him anywhere he went, so Haseeb began to learn, which landed him a job at a company contracting with the U.S. Army in 2007. In 2013, he became an interpreter for the United States Marine Corps, and met Gunnery Sergeant Hugh Tychsen.

Having completed three tours in Iraq, Tychsen was well versed in combat. Afghanistan, though, was a relatively new experience, so he wasn’t sure what to expect working as a mentor/advisor alongside Haseeb.

What he found was a brother.

Haseeb brought the gunnery sergeant packs of Marlboro cigarettes and cases of Monster Energy drinks, and he and Tychsen would talk late into the evening about life and philosophy

“I loved Hugh. He was family. It’s why I went into meetings first [in the event shooting began]. He had a wife and child at home. I was single. He had more to lose.”

While Haseeb’s sentiments moved Tychsen, the gunnery sergeant also wanted to impart the value and potential he saw in Haseeb’s life. As the months stretched on, he encouraged, validated, and mentored his Afghan friend, sharing stories about America and life there. This led Haseeb to approach Tychsen about an immigrant visa to relocate to the United States.

Tychsen wasn’t even aware of the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV), which grants permanent residence to people who aided the U.S. government abroad. When a Marine captain approached Tychsen about helping another interpreter get a visa, he learned how to obtain a SIV. Tychsen now understood that for Haseeb to immigrate to the United States, he would need Chief of Mission (COM) Approval, which required a letter of recommendation by a U.S. Citizen who served as his supervisor.

Prior to leaving Afghanistan, Tychsen gave Haseeb what he needed to begin his own SIV application—two copies of his letter of recommendation for Haseeb’s unwavering commitment to U.S. Forces in Afghanistan.

The two men would not see each other again for four years.

…

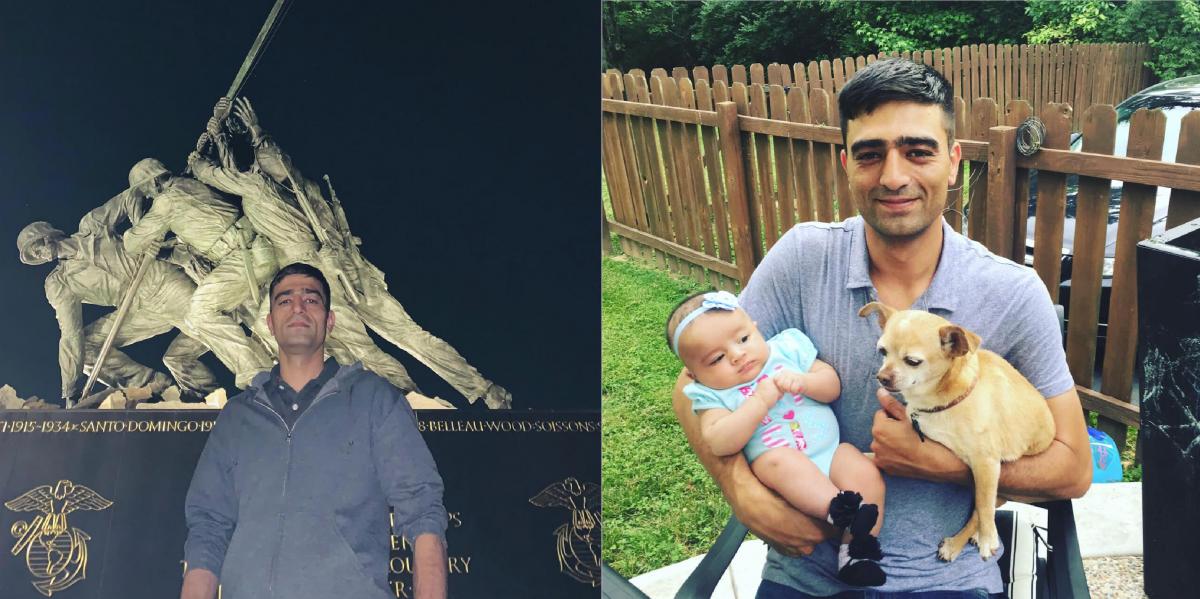

In 2017, after four years of back and forth with the State Department, Haseeb’s SIV status was granted. While Haseeb’s family encouraged him to move to California or New York, Haseeb was uncertain of the culture in American cities. He reached out to Tychsen, who now worked for a major company but often battled his own demons from war.

Haseeb’s call sparked a sense of purpose and clarity for Tychsen. He knew he could help his former interpreter and friend. “Dude, move to Saint Louis and live near me,” Tychsen told Haseeb.

When Haseeb’s mother encouraged him to take Tychsen up on his offer—and insisted that it was the will of Allah—Haseeb packed up his wife and daughter to move close to his old friend.

The day Haseeb arrived at the airport, he broke down in tears. Tychsen had brought a huge crew of friends and families, as well as a local television station, to welcome him to the United States. Both men embraced for the first time in years and cried together as they met each other’s families for the first time.

Tychsen arranged to move Haseeb and his family into an apartment and got him a job as a contractor, and Haseeb’s new American life began to take shape. At the same time, both men sensed that they needed to help other Afghans who had served as contractors and interpreters and remained in Afghanistan and in danger.

Tychsen and Haseeb discovered a new mission: wading through the murky waters of immigration to help fellow Afghan allies moved to the United States.

In 2017, Tychsen and Haseeb began paperwork for 74 families, helping all of them earn COM approval. It was a feat unmatched by even the most prolific organizations working with Afghan immigrants. The two combat veterans were hopeful that with enough time and properly navigating government bureaucracy, they’d bring these families to the United States. But when the U.S. military’s withdrawal and fall of Afghanistan occurred in August 2021, a profound sense of urgency emerged.

Tychsen and Haseeb joined a growing community of veterans and other concerned Americans to help evacuate Afghans, a campaign known as Digital Dunkirk. However, they found that evacuating the families was next to impossible. Tychsen sent letters to the State Department, contacted non-governmental organizations, non-profits, and just about anyone who would listen. He found an ally one afternoon in Peter Lucier of Team America Relief, who also lived in the St. Louis area. Peter realized Tychsen had close to 75 families far enough in the evacuation pipeline that they might get some out.

Tychsen and his team received approval to evacuate a U.S. contractor named Mir Amri and his family. On August 27, 2021, they instructed Mir Amri to bring his family to Kabul International Airport’s Abbey Gate.

But tragedy struck. A suicide bomber detonated himself at the gate, killing 170 Afghan civilians attempting to flee Afghanistan and 13 U.S. service members. Mir Amri took shrapnel to his face and his family absorbed the blast impact, concussing them all. The family survived, but in the ensuing chaos, the evacuation didn’t happen and Mir Amri remains stuck in Afghanistan.

The event—and the U.S. withdrawal—rattled Tychsen and Haseeb, but also steeled their resolve not to abandon our Afghan allies even as the war and evacuations officially ended. Instead of despairing, they got four families out of Afghanistan.

Knowing that new Afghan refugees would face the same struggles he did, Haseeb started his own contracting company to employ fellow Afghan refugees when they emigrate to the United States.

“People often ask me, ‘Did we [Americans] really help or change your country?’” Haseeb states from his work van. “I was there during the Taliban and it was terrible. With Americans, we had roads, electricity, telephones, and internet… we didn’t have any of that before.”

Many veterans of the Afghan War agonize over the betrayal of leaving their interpreters to fend for themselves against the Taliban. The fall of Kabul led to a record numbers of calls from veterans to the VA’s crisis line. Reports show that the return of Taliban rule has brought increased human rights violations; as the country teeters on the edge of famine, Afghanistan has become the world’s largest humanitarian crisis. Getting SIV applicants out of the country has become so difficult that there are 35,000 names in just Peter Lucier’s database.

Tychsen sees the red tape and logistical nightmares, but his Marine Corps esprit de corps keeps him hopeful.

“There’s no love, respect, or honor in leaving people behind -- that’s the crux of our military code. [But] the government doesn’t respond to emails. We send verification IDs up to them daily, sometimes as many as three times, and they lose it all. The people in the government are anything but helpful, so it’s up to us once more [to win this war].”

While Haseeb and Tychsen fight to get their SIV applicants stateside, they’re also waging war against the humanitarian crisis by feeding 150 families starving in Afghanistan. Haseeb and Tychsen send money, using undercover contacts and hidden locations inside Afghanistan to get these families—who are on the brink of starvation—money for food.

“One hundred dollars feeds an Afghan family for a month!” Haseeb exclaims. “An entire month!”

Haseeb now speaks at churches and non-profits across his adopted community of St. Louis to clothe and feed those we left behind, partnering with unique refugee entities like Oasis International.

Haseeb doesn’t pull punches about Afghanistan, the war, and the ongoing crisis. “In America, you support your children for eighteen years. You gave us [Afghans] two extra years,” he says. “We need to be able to stand up on our own. Yes, there was corruption, education was taken advantage of, but these people still need help. They are like sleeping lions, but we cannot abandon starving families and those who were next to American soldiers.”

Tychsen smiles at Haseeb’s passion, so reminiscent of the warrior he knew in Afghanistan, but now on a new mission— feeding desperate families and getting our deserving allies to the United States.

These days, Hasseb no longer keeps a bullet for himself. Instead, he has a new outlook on life. “Hugh [Tychsen] is a blessing. I never thought I’d be in America and have all my dreams come true. I want that for the others,” He states.

Perhaps that’s the lesson veterans can learn from Haseeb and Tychsen: We can find a new mission, meaning, and purpose when we return stateside. Combat doesn’t have to be the pinnacle of our service. We can write letters of recommendation to help our allies. We can wage war against unjust practices to bring those who fought beside us to a new home. We can practice individual acts of generosity and urge our leaders to make welcoming Afghans a priority.

The war in Afghanistan may be over. But for our Afghan allies, it’s just beginning.